United for football, divided right after?

“United by football. United in the heart of Europe.” UEFA bosses picked the slogan to show their tournament would welcome everyone at a time when less welcoming politics are on the rise around host nation Germany. A few months ago, a group of young people earned their 15 minutes of infamy by changing the lyrics to L’Amour Toujours to vile anti-migrant abuse. A survey asking Germans if they’d like their team to feature more white players was dismissed by Germany’s head coach as what it was: racist.

Worryingly, one in five respondents thought their team had too many migrants and that 25-year-old dance hit has been trending on Spotify within Germany. All while the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerged as the country’s second-largest force in the European Parliament and is set to win state elections later this year despite a series of scandals that left little doubt about the party’s ideology, intentions, and alliances.

The organizers would be keen to avoid any of these embarrassing developments making their way into the spotlight that’s shining on Germany this month. Just a few months ago, far-right supporters of Lazio, in town for a fixture against Bayern, sang Italian fascist songs at the Munich venue where Hitler founded the Nazi Party. You would think more people would notice if they did so this summer.

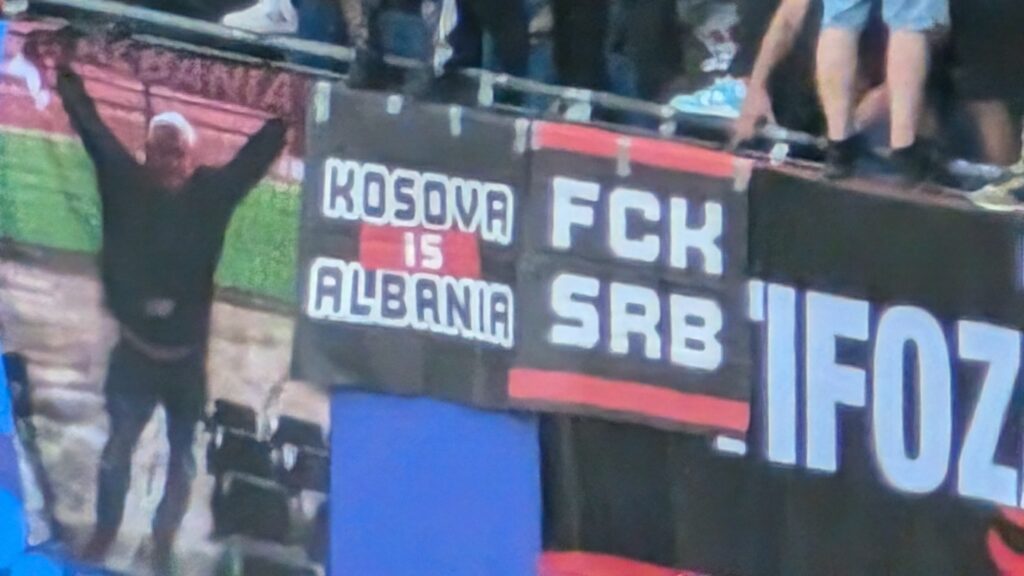

Some of the usual feuds emerged like clockwork around the tournament. Some Croats and Albanians united indeed, but to chant abuse against Serbs, with a banner clearly targeted at Serbia hanging unbothered from the red-and-black side of Volksparkstadion.

(Photo: M. Moschopoulos)

In Leipzig, an Italian supporter asked Croats to ‘return’ Rijeka to them with a banner briefly displayed before kick off. The city and its neighbouring regions of Istria and Dalmatia, parts of Yugoslavia and then Croatia since World War II ended, have long been part of Italian nationalist propaganda. Italy’s current foreign minister found himself in hot water when, while serving as European Parliament president, he used words which seemed to “interfere with the territorial integrity of Croatia” – as Croatia’s PM Andrej Plenković put it.

(Photo: M. Moschopoulos)

Other nations did not even have to qualify to find themselves in the crosshairs: Some Serbs and Slovenes were caught on camera denying Kosovo’s independence, while an Albanian player led chants against North Macedonia. You’d think UEFA got away with it when Georgia beat Greece to appear instead in a group stage fixture against Turkey, but somehow a few fans managed to start a fight in the stands anyway.

Berlin’s Olympiastadion, historically charged as it is, was the venue for the debut of another concerning banner. A few minutes before their side’s match against Poland came to an end, a group of Austrian supporters unfurled a banner reading ‘Defend Europe’, the slogan of the far-right and anti-migrant Identitarian movement. While the football federation was quick to distance itself from the banner’s content, their country might be electing a far-right Chancellor in September.

Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) is on course to win elections in September. The prospect of an Austrian far-right Chancellor was once so repulsive in 2000 that the rest of the European Union refused “any official bilateral contacts at political level with an Austrian government integrating the FPÖ.” This autumn, FPÖ politicians could join far-right ministers from Finland, Italy and the Netherlands – or maybe even France – in Council meetings chaired by Viktor Orban’s people.

When Donald Trump won the 2016 election, a 1935 novel by Sinclair Lewis became a bestseller on Amazon. “It Can’t Happen Here” follows an American politician who promises to make the country great once more and then uses his power to become a dictator. At the time, it would be tempting to think that had the book done better sooner, there would be no real-life adaptation of its plot. Given the significant chance of a second Trump presidency four years after the Capitol attack, there is no reason to believe that would be the case.

In Europe too, many people thought it can’t happen here. Far-right parties are in government from Finland to Croatia, once-dominant conservative parties are striking deals with nationalists to retain power, and rights and liberties are under threat across the continent. For Germany, the prospect of the far-right winning power is even more of an anathema, given the country’s decades-long efforts to educate its youth about the dangers of nationalism (dismissed as a ‘cult of guilt’ by AfD officials).

This included a reluctance to fly the country’s flag, Angela Merkel once confiscating one waved around by a jubilant CDU colleague after the 2013 election win. Some credit Germany’s success in the 2014 World Cup for an uptick in public displays of the German flag. In 2017, even Merkel’s party printed the black, red and gold stripes on their posters. Now, even the centre-left SPD included a small flag for the latest vote. Given how few German flags one can find on Berlin’s balconies, it still feels like their presence is a statement beyond football.

(Photo: M. Moschopoulos)

Musa Okwonga pointed out how few football writers seemed interested in the political reality surrounding UEFA Euro 2024 venues, especially when compared to the excellent journalism that alerted the world to the plight of migrant workers and others in Qatar. His own essay before the tournament kicked off is a rare example of the kind of writing missing this summer. While many have pointed out the ghosts of Germany’s past, hard to ignore when you’ve got fixtures at the 1936 Olympics stadium and the former Adolf-Hitler-Kampfbahn, few have looked at the demons of its present and future.

Germany remains a diverse country that’s home to millions of migrants. The UEFA Euro 2024 has been a showcase of that, the atmosphere in Croatia’s opener in Berlin against Spain feeling as if we were in Zagreb’s Maksimir Stadium, just bigger and louder. Turkey and Ukraine can count on the support of millions of their compatriots living in the tournament’s host cities, while several national sides line up this summer with players born in Germany: Hungary, Spain, Croatia, Albania, Serbia, and Turkey. The vast majority of fans have enjoyed themselves and each other’s company at the tournament’s stadiums, most fretting over issues such as the refusal of Hamburg’s vendors to take credit cards, Gelsenkirchen’s tram network, and why VAR can’t be this fast at home.

A couple of months after travelling fans leave and migrant supporters go back to their day-to-day business, the states surrounding Berlin and Leipzig go to the polls. The AfD is projected to win in both. A ‘what if’ alternative history exhibition in a Berlin museum speculates that without Germany there would be no project to unite Europe. Football bosses claim the country is Europe’s heart. Losing Germany to the far-right could indeed be fatal for our continent’s unity.